Three options for a quality grocer like ICA or Kesko?

Image source: Kesko and ICA

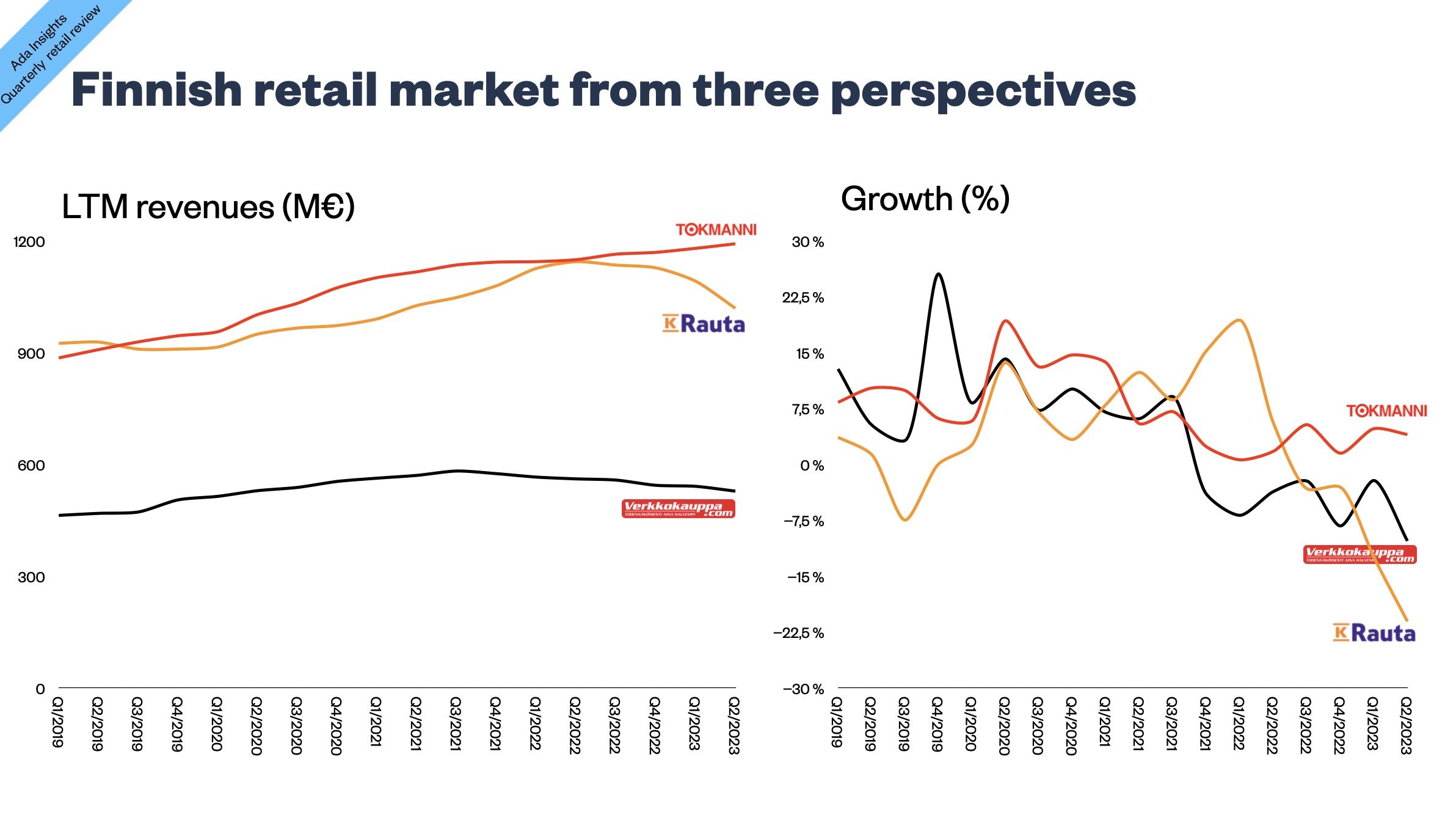

After fabulous growth and profitability during the pandemic, many quality-oriented traditional (referred to as full-line in the UK) have faced severe problems in matching the market growth, let alone inflation.

Kesko in Finland and ICA in Sweden were among the biggest winners during the pandemic.

Since 2021, both companies have struggled, leading to big losses in market share. Inflation and the subsequent customers’ focus on price have led the main rivals, Willy's and Prisma, to outgrow the market. The German discounters Lidl and Aldi have enjoyed strong growth in almost every market.

In Sweden some have even argued that ICA is in panic. Finally in March ICA launched a price war with 300 products. That is not sufficient to turn the market share back to growth. Kesko in Finland has refrained from big and public actions to curb the price image. Naturally, the company has done a lot behind the scenes. Still, no major initiative has been communicated to the customers besides some marketing around low prices alongside high-quality products.

How long and difficult this price-led period will become remains to be seen. Likely, the bad times are not over soon. Here are some thoughts on how these Nordic grocery giants could approach the difficult times.

Direct price war

Image source: Tesco

Big grocers' obvious and most used strategy is the full-on direct price war with the price-driven companies. It would be expensive to drive the overall price level low enough to become comparable to the discounters.

Willy's and Prisma, let alone Lidl, are structurally much more efficient and thus have more leeway to respond to changes in price. Prisma is a cooperative, and Lidl is a privately held and family-owned company. Thus, they don’t have external shareholders to please.

Many retailers have initiated a price war through price matching, guarantees, and locks. There are two ways to do that.

Firstly, the approach used by the British grocers is direct price-matching to Aldi (the cheapest option). It is not recommendable to promote your competitor and strengthen their price image. The other problem with the approach of the British grocers is that they have increased the number of products rather slowly. They started with a couple of hundred products and gradually increased it to 600.

The other approach is used by Albert Heijn in the Netherlands. They have not compared prices to any named grocer but to “the lowest price in the market.” This does not play into any grocer's price image. Albert Heijn has expanded the price guarantee assortment more rapidly, quickly to 1 800 products and recently to 2 000. This is comparable to the full assortment of a discounter.

This has given Albert Heijn possibilities in advertising to promote how you can have as many products as in a discounter’s store with the same prices and everything else that Albert Heijn carries and in the beautiful stores.

This way is expensive. Tesco reported a 7% decline in operating profits as a result. Also, Royal Ahold has seen European operating margins come down partly due to the investments in price.

Would this help generate the market share and volume gains that they require? Tesco has not been able to win market share but has been losing the least among the big grocers in the UK. On the other hand, Albert Heijn in the Netherlands won market share against Aldi.

Image source: Albert Heijn

Regarding the competition in Finland and Sweden, Willy's, Prisma, and Lidl are structurally more competitive than ICA or Kesko.

In order to become truly price competitive, Kesko and ICA would need to make big structural changes. Narrowing of the assortment is one place, and the other is the organizational structure with entrepreneurs and quite a big head office.

One should remember that the seeds of problems are sown during the good times. However, the greatness of the coming decades is built during the crisis. Is this a big enough crisis for Kesko and ICA to make serious changes?

Probably not, given the good profitability of both. Both are coming down from really high profitability to more normal levels of profitability. Normally businesses need an existential crisis, such as for S-Group in the 1980s, to generate needed changes for long-term success.

Ride it out: focus on the core customer

When others zig, is it good to zag? As everyone is fully focused on price, one must remember that many customers can still buy food normally.

In 2015, during the big price promotional campaign by S-Group, Halpuuttaminen, Kesko acted swiftly but did not attack with a full-on response. The company did do price reductions reactively, but no major offense against the growth of S-Group.

Image source: S Group

The next year, 2016, Kesko did go on to acquire a convenience chain competitor. Eventually, the good times followed, and the focus on price faded. That led to a three-year period of market share growth between 2018-2020.

This time with the less reactive approach, some entrepreneurs would struggle mightily, and some may even go bankrupt. It would also acknowledge that the companies are at the mercy of market fluctuations.

On the other hand, focusing more on quality-conscious customers would be a good strategic choice. Unfortunately, there is little room for strategic differentiation in the red ocean type of grocery competition as there is little room to expand internationally.

Lidl differentiates itself strategically, and it can go through periods of lower growth or even market share loss and still remain committed to the focused business model. If one market declines, Lidl can generate growth from other markets where it operates and even expand to new markets.

Thus, for Kesko and ICA focusing on quality-oriented customers would become expensive as volumes would drop significantly. Are these companies with big market shares serving customers from all walks of life ready to pass on big chunks of market share?

Innovations: something new

The third option is to invest in something new. This can be a new revenue stream on top of the existing channels. One such option is to tap into the growth of out-of-home eating. There are two main possibilities for this: S-Group operates restaurants and benefits directly from the eating-out trend, whereas Tesco and Kesko lead the food service wholesaling market in the UK and in Finland.

Image source: Kespro

Therefore, Finland's out-of-home growth does not provide similar big growth opportunities for Kesko as it does for ICA, which does not have a wholesaling operation or restaurants. For Kesko, the big growth opportunity lies in internationalising the wholesaling arm Kespro (**LINK**).

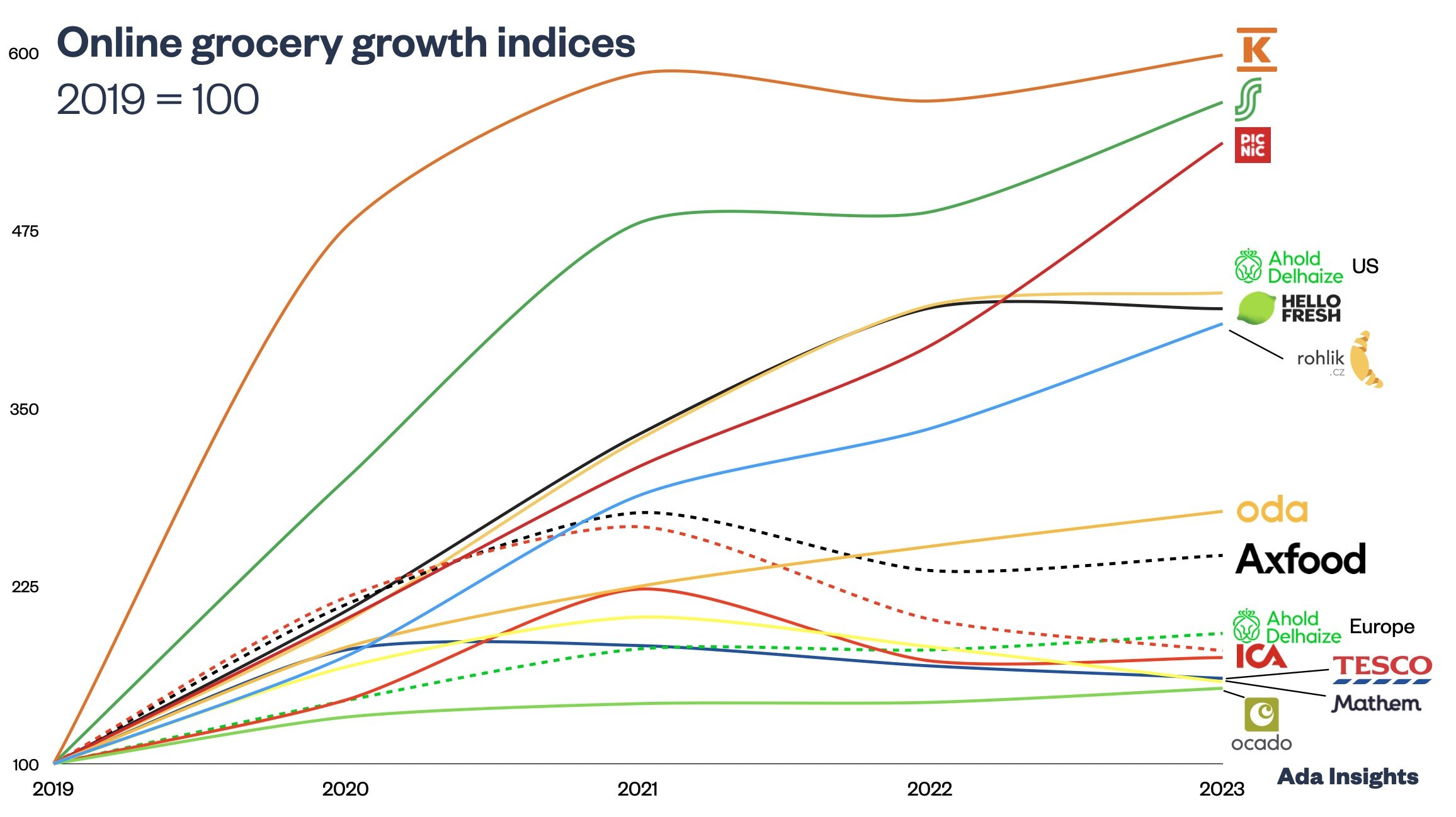

The longer-term innovation opportunity lies in the online channel. Kesko and ICA have large market shares in the nascent online markets in Finland and Sweden. Due to the small online channel share, the market does not look attractive for a big organisation.

However, as mentioned in this text, the seeds of future success are sown well in advance and often in difficult times. Online represents a similar conceptual shift as the big stores were in the early and mid-1980s. A more efficient but still small concept stoked great excitement in the industry.

In the 1970s and 1980s, many retailers saw the potential of the nascent concept of big stores. These companies were often newly established (Asda, Carrefour or Walmart) or struggling underdogs (Tesco & S-Group). They double-down on the big stores and eventually built their market dominance around the growth of the concept in the preceding decades.

Online grocery retailing will most likely represent a similar shift. Just like with big stores, the unfolding of the change will take time. Big and profitable retailers can't double down on something contradictory to their existing businesses.