What Oda’s withdrawal tells us?

Today marked the unfortunate, but unfortunately not surprising, the decision by Oda to cut down losses and shut down their online store in Finland. The online channel in Finland is still in its infancy, and at the same time, the market is notoriously difficult to enter, with one of the world’s highest concentrations in the grocery trade.

Whenever a company enters a new market by selling groceries, it takes time and money. Groceries is a category deeply ingrained in the customer routines that it is challenging to open something new. Even new stores opened by existing chains can take time to become profitable, let alone introducing new chains.

Grocery history is littered with big companies with ambitious plans to conquer new countries after big success in the home market.

During its heyday, Tesco challenged Walmart head-on in the United States. This became a multibillion-pound mistake that derailed the entire Tesco business for years.

Walmart itself entered the UK by acquiring Asda in the late 90s with high hopes of capturing the United Kingdom. After two decades, the world’s biggest retailer had not been able to gain any significant market share. In 2021 Walmart sold Asda to two British entrepreneurs.

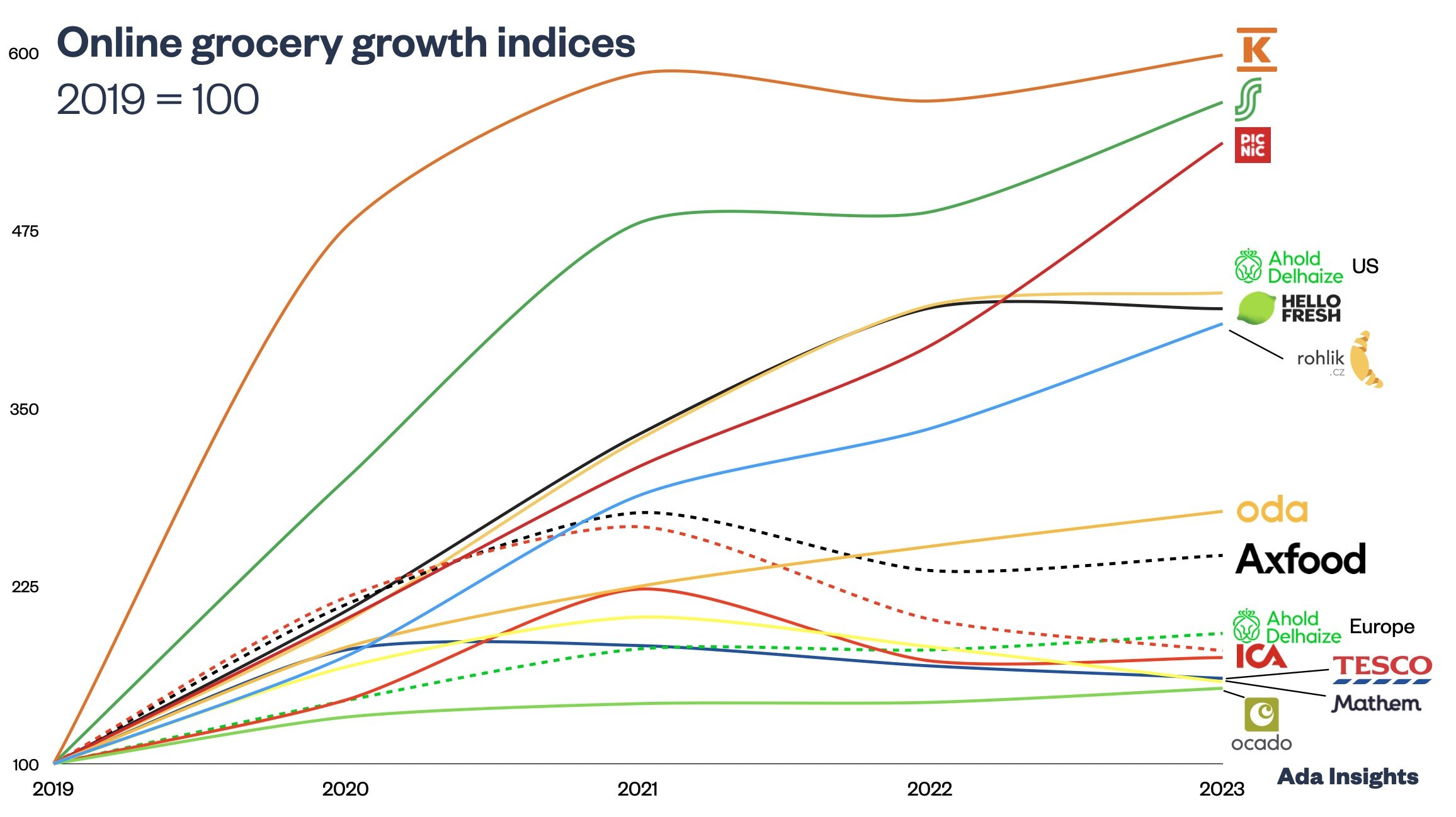

Oda came to Finland with high hopes during the pandemic. The world has changed quite dramatically since then, especially from the perspective of an online grocer. The massive boost for online, given by the pandemic, has faded. At the same time, the war in Ukraine and the subsequent explosion of inflation and interest rates have disrupted the financing for rapidly growing online grocery players.

Was Oda’s entry a failure?

Only a couple of weeks ago, I analysed the recently published numbers for the first year of Oda in Finland. The figures were encouraging when compared to other online grocery launches in Europe. Oda became one of Finland’s biggest, if not the biggest, online grocery challengers in one year.

Thus, one can say that Oda did not fail during its first year in Finland. However, it is not enough to have growth. One also needs deep pockets and patience to enter the Finnish grocery market.

When Oda launched last year, it was the first company to enter the Finnish grocery market since Lidl opened in Finland two decades prior. Lidl’s foray into Finland offers a great comparison to the case of Oda.

Market entry takes time and costs, a lot

For the first seven years of Lidl’s journey in Finland, the company generated more than 70 million euros in losses. 2007 was the first one when Lidl Finland could report a profit of seven million euros (1,3% profit margin). However, the company fell back to red for the next year, 2008, with losses of 7,4 million euros.

It is easy to imagine the discussions between German headquarters and the Finnish country leadership about how the business should be dragged to profitability or should the project be abandoned.

As we all know, 2010 was a watershed moment for the company. The company had become profitable the previous year but saw a slight decrease in revenues. In the 2010s, Lidl entered a period of highly profitable and rapid growth. Between 2010 and 2015, Lidl doubled revenues and transformed the poorly profitable business into a company with 5+% profit margins.

In 2021, Lidl produced almost 95 million euros in profits. It is almost 40% more than all the losses combined during the first decade.

This explosive growth took a decade to start.

How about Oda?

Was Oda impatient to abandon the Finnish market only after a year? That would be a far too easy answer.

One has to remember that Oda is a 200+ million euro company, whereas Lidl was a grocery giant with tens of billions of euros in revenue. Lidl also had experience in opening dozens of new markets before Finland. For Oda, Finland was the first new market after Norway.

It was obvious that if Oda were ever to gain meaningful market share in Finland, it would take years and cost millions.

The disruption of the financial markets and subsequent crash in Oda’s valuation has impacted the company’s future plans. With limited financing and new markets (Finland and Germany) bleeding money, it was clear that something needed to change.

As things come to a head in Norway, it is evident that the German operation was prioritized over the Finnish market. That boils down to three main reasons:

The business potential in only Berlin is vastly bigger than in Finland. With more than 80 million people living densely offers a huge market.

The online grocery market is nascent in both countries. But Germany is advancing much more rapidly than Finland. Germany is, after all, the home of Zalando and the second-biggest market for Amazon. Now the country has seen a flurry of new online grocery players. Alongside Oda, Picnic and Knuspr (part of the Rohlik group) are advancing in the country.

Sourcing terms in Finland are challenging, to say the least. In Germany, multiple local players can offer decently competitive sourcing terms for a new grocer. This is the biggest barrier to entry into the Finnish grocery market.

The difficulty of sourcing in a concentrated market

Finland is the most concentrated grocery market in the Western world. New Zealand is the only other market with more than 80% concentrated for two big players. In other Nordic countries, there are at least three significant players. This has offered pure-play online grocers a lifeline. They have partnered with a challenger in sourcing. For Oda in Norway, this was Rema1000. For Mathem in Sweden, it has been Axfood.

Sourcing is probably the most crucial element for success in grocery retailing. For S-Group’s spectacular rise in the 90s, combining sourcing power with another challenger (Eka) was essential to challenge the current incumbent, Kesko. For Oda, it would have been essential to get somewhat competitive sourcing prices for a fair chance to compete in the market.

The Commerce Commission of New Zealand also identified the difficulty in getting competitive prices as one of the most critical barriers to entry.

The market share concentration for two big players in Finland is a complex topic. On the one hand, it is good for the consumer in the form of many stores and within very accessible (and expensive) locations. The stores in Finland are also beautifully designed and filled with huge assortments of products.

On the other hand, the grocery industry in Finland is very profitable compared to its European peers. That profitability seems to have increased as the market has concentrated (as one would learn in introductory economics).

As long as the sourcing of groceries from the industry to selling to the consumers is controlled from end to end by two giant players, the market won’t have significant new players.

The restaurant sector does not have a similar structure. We see a dynamic market with many new players entering simultaneously as some fail.

Oda’s experience is a dangerous example for any grocer considering entering Finland.